Swimmer's Ear (Otitis Externa)

Overview

What Is Swimmer's Ear?

Swimmer's ear is an infection of the ear canal, the passage that carries sounds from the outside of the body to the eardrum. It can be caused by different types of germs.

Causes

What Causes It?

Swimmer's ear (or otitis externa) is common in kids who spend a lot of time in the water. Too much moisture in the ear can irritate the skin in the canal, letting bacteria or fungi get in. It happens most often in summertime, when swimming is common.

But you don't have to swim to get swimmer's ear. Anything that injures the skin of the ear canal can lead to an infection. Dry skin or eczema, scratching the ear canal, ear cleaning with cotton swabs, or putting things like bobby pins or paper clips into the ear can all increase the risk of otitis externa.

And if someone has a middle ear infection, pus collected in the middle ear can drain into the ear canal through a hole in the eardrum and also cause it.

Signs & Symptoms

What Are the Signs & Symptoms?

Ear pain is the main sign of swimmer's ear. It can be severe and gets worse when the outer part of the ear is pulled or pressed on. It also may be painful to chew. Sometimes the ear canal itches before the pain begins.

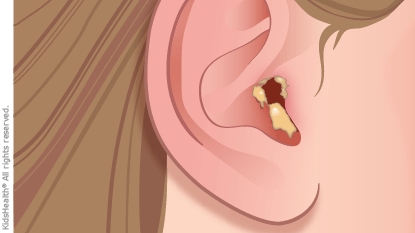

Swelling of the ear canal might make a child complain of a full or uncomfortable feeling in the ear. The outer ear may look red or swollen, and lymph nodes around the ear can get enlarged and tender. Sometimes, there's discharge from the ear canal — this might be clear at first and then turn cloudy, yellowish, and pus-like.

Hearing might be temporarily affected if pus or swelling blocks the ear canal. Most kids with swimmer’s ear don’t have a fever.

When Should I Call the Doctor?

Call your doctor right away if your child has any pain in the ear with or without fever, decreased hearing in one or both ears, or abnormal discharge from the ear.

Treatment & Care

How Is It Treated?

Treatment depends on how severe the infection is and how painful it is. A health care provider might prescribe ear drops that contain antibiotics to fight the infection, possibly mixed with a medicine to reduce swelling of the ear canal. Ear drops for swimmer’s ear are usually given several times a day for 7–10 days.

If a swollen ear canal makes it hard to put in the drops, the doctor may insert a tiny sponge called a wick to help carry the medicine inside the ear. In some cases, the doctor may need to remove pus and other buildup from the ear with gentle cleaning or suction. This lets the ear drops work better.

For more severe infections, health care providers may prescribe antibiotics taken by mouth and might want to run tests on discharge from the ear to find which bacteria or fungi are causing the problem.

Over-the-counter pain relievers often can manage ear pain. Once treatment starts, your child will start to feel better in a day or two. Swimmer's ear is usually cured within 7–10 days of starting treatment.

How Can I Help My Child Feel Better?

Ear infections should be treated by a doctor. If not, the ear pain will get worse and the infection may spread. At home, acetaminophen or ibuprofen may help ease pain.

Follow the health care provider's instructions for using ear drops and oral antibiotics, if they're prescribed. It's important to keep water out of your child's ear during the entire course of treatment. You can use a cotton ball covered in petroleum jelly as an earplug to protect your child's ear from water during showering or bathing.

Prevention

Can Swimmer's Ear Be Prevented?

Using over-the-counter drops of a dilute solution of acetic acid or alcohol in the ears after swimming can help prevent swimmer's ear, especially in kids who get it a lot. These drops are available without a prescription, but should not be used in kids who have ear tubes or a hole in the eardrum.

To avoid injuring an ear, young kids should not clean their ears themselves. Also, never put objects into kids' ears, including cotton-tipped swabs. Dry ears after they get wet using a hair dryer on the cool setting.

Reviewed by: Amy W. Anzilotti, MD

Date Reviewed: Apr 20, 2023