Torticollis in Infants

Torticollis is a stiff neck that makes it hard or painful to turn your head. In older kids and adults, it can happen after sleeping in a funny position. Babies can be born with a stiff neck, but the condition is a little different and not painful.

What Is Torticollis in Infants?

A baby can be born with a type of torticollis (tor-tuh-KOL-is) called congenital muscular torticollis. Most don't feel any pain from it. And the problem usually gets better with simple position changes or stretching exercises done at home.

What Causes Infant Torticollis?

Doctors aren't sure why some babies are born with torticollis and others aren't. It might happen from being cramped inside the uterus or in an unusual position (such as being in the breech position, where the baby's buttocks face the birth canal).

These things can put pressure on a baby's sternocleidomastoid (stir-noe-kly-doe-MAS-toyd) muscle (SCM). This large, rope-like muscle runs on both sides of the neck from the back of the ears to the collarbone. Extra pressure on one side of the SCM can make it tighten, which makes it hard for a baby to turn the neck.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Infant Torticollis?

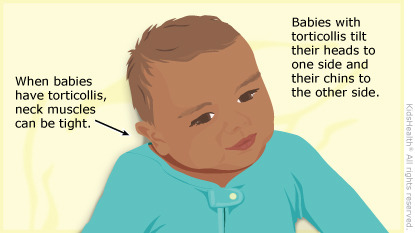

Babies with torticollis will act like most other babies except during activities that involve turning their head. When they’re about 2–4 weeks old, a baby with torticollis might:

- tilt the head in one direction (this can be hard to notice in very young infants)

- not fully turn their head to follow you

- if breastfed, have trouble breastfeeding on one side (or prefer one breast only)

- work hard to turn toward you

Some babies with torticollis develop a flat spot on the head (positional plagiocephaly) from lying in one direction most of the time. In some, the neck, jaw, and face also might be uneven. Some babies develop a small neck lump or bump, like a "knot" in a tense muscle. These things tend to go away as the torticollis gets better.

How Is Infant Torticollis Diagnosed?

Your doctor will do an exam to see how far your baby can turn their head.

How Is Infant Torticollis Treated?

If your baby does have torticollis, the doctor might teach you neck stretching exercises to practice at home. These help loosen the tight SCM and strengthen the one on the other side, which is looser and weaker due to underuse. This will help to straighten out your baby's neck.

Sometimes, doctors suggest taking a baby to a physical therapist for more treatment.

After treatment starts, the doctor may check your baby every 2–4 weeks to see if the torticollis is getting better.

Helping Your Baby at Home

Encourage your baby to turn the head in both directions. This helps loosen tense neck muscles and tighten the loose ones. Babies cannot hurt themselves by turning their heads on their own.

Here are some exercises to try:

- When your baby wants to eat, offer the bottle or breast in a way that encourages your baby to turn away from the favored side.

- When putting your baby down to sleep, position them to face the wall. Because babies prefer to look out onto the room, your baby will actively turn away from the wall and this will stretch the tightened muscles of the neck. Remember — always put babies down to sleep on their back to help prevent SIDS.

- During play, draw your baby's attention with toys and sounds to make them turn in both directions.

Don't Forget "Tummy Time"

Laying your baby on the stomach for brief periods while awake (known as "tummy time") is an important exercise. It helps strengthen neck and shoulder muscles and prepares your baby for crawling.

This exercise is especially useful for a baby with torticollis and a flat spot on their head, and can help treat both problems at once. To do it:

- Lay your baby on your lap for tummy time. Position them with their head turned away from you. Then, talk or sing to your baby and encourage them to turn and face you. Practice this exercise for 10–15 minutes three times a day.

What Else Should I Know?

Most babies with torticollis get better through position changes and stretching exercises. But be patient — it can take up to 6 months to go away completely, and in some cases can take longer.

Reviewed by: Melanie L. Pitone, MD

Date Reviewed: Jan 1, 2023